Tell Me :

Talk

on the other hand, he could be spending his spare time exclusively playing cricket and/or socializing and not working hard to make exciting new products for public consumption...

I love that shot - thanks for posting the whole thing, bbj

Many films start out slow and then build as the word gets out. I plan to see it next weekend.

Talk about your favorite band.

For information about how to use this forum please check out forum help and policies.

Re: Mick: 'Get On Up' film & HBO TV series

Posted by:

latebloomer

()

Date: July 25, 2014 16:54

Mick's facebook page:

On the set of the HBO pilot directed by Marty Scorsese - somewhere in long island! Mick

On the set of the HBO pilot directed by Marty Scorsese - somewhere in long island! Mick

'Get On Up'

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: July 25, 2014 16:56

Mick and Chadwick Boseman at the 'Get On Up' premiere, July 21.

Dave Allocca/Starpix

_____

All videos 'Get On Up' - interviews, trailers, TV commercials...even B-roll from the premiere > [www.traileraddict.com]

Dave Allocca/Starpix

_____

All videos 'Get On Up' - interviews, trailers, TV commercials...even B-roll from the premiere > [www.traileraddict.com]

Mick & Chadwick Boseman - Billboard, August 2

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: July 25, 2014 18:52

Mick Jagger & Chadwick Boseman Talk 'Get On Up,' James Brown and a Rolling Stones Biopic

By Tatiana Siegel | July 25, 2014

Joe Pugliese

What's it like when Mick makes you his movie's leading man? The legendary rocker-turned-Hollywood producer and 'Get On Up' star Chadwick Boseman reveal what went on behind the scenes to bring James Brown back to life.

"It's good to be back," says Mick Jagger, sweeping a hand across the grand view in front of him at the historic Apollo Theater in Harlem. The Rolling Stones frontman, who moonlights as an increasingly busy Hollywood producer, is here to discuss Universal's James Brown biopic Get On Up, two days before the film premieres at the same venue. It has been years since Jagger, who turns 71 on July 26, last visited the majestic Apollo. He can’t recall exactly when.

"I came a lot like in the ’80s, and then it was closed for repairs a lot," he says. It's clear that Jagger is feeling slightly nostalgic. "Over the years, I've been in and out of here quite a few times."

For Jagger, Get On Up -- directed by Tate Taylor of The Help and opening Aug. 1 -- proved to be a formidable journey, taking eight years to reach the big screen. The project has been around longer than that, though — at least 12 years. Producer Brian Grazer, fresh off a best picture Oscar win for A Beautiful Mind, signed a deal with Brown in 2002 to secure the Godfather of Soul's life rights. A parade of directors like Spike Lee and actors including Eddie Murphy and Chris Tucker floated in and out of the Brown orbit, with things becoming more complicated after the three-time Grammy-winning icon died in 2006, with his estate in disarray (a court battle between his widow and his children continues to this day, with the South Carolina Supreme Court saying the estate has an undetermined value between $5 million and more than $100 million).

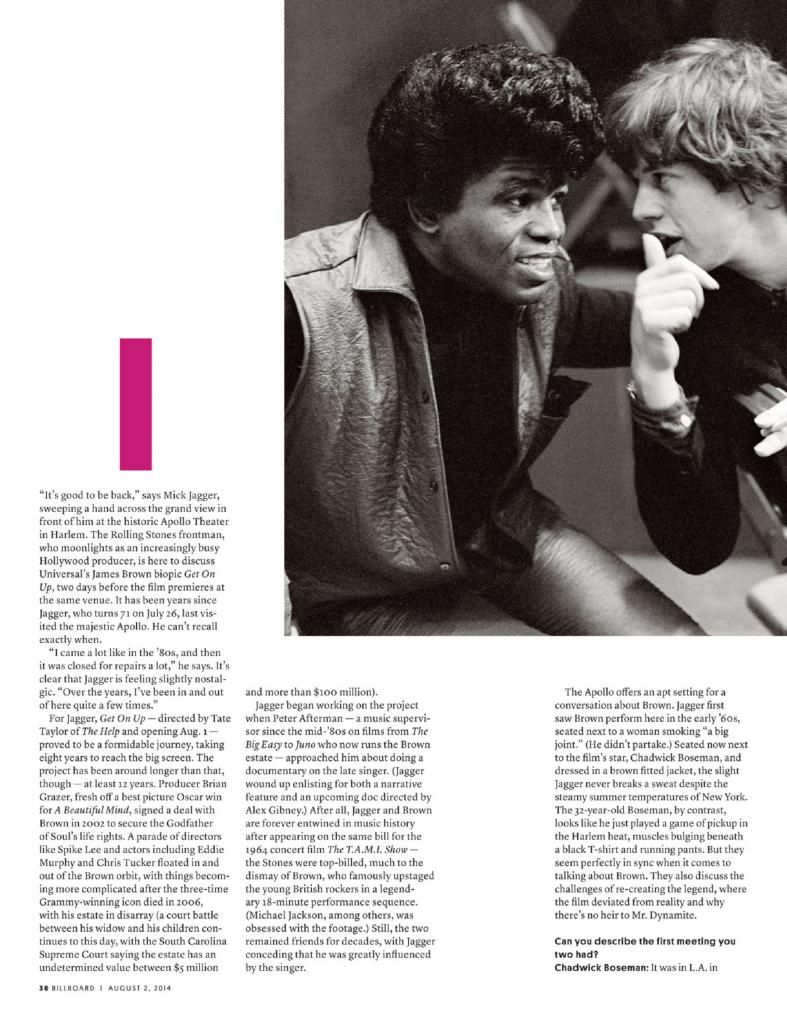

Jagger began working on the project when Peter Afterman -- a music supervisor since the mid-'80s on films from The Big Easy to Juno who now runs the Brown estate — approached him about doing a documentary on the late singer. (Jagger wound up enlisting for both a narrative feature and an upcoming doc directed by Alex Gibney.) After all, Jagger and Brown are forever entwined in music history after appearing on the same bill for the 1964 concert film The T.A.M.I. Show — the Stones were top-billed, much to the dismay of Brown, who famously upstaged the young British rockers in a legendary 18-minute performance sequence. (Michael Jackson, among others, was obsessed with the footage.) Still, the two remained friends for decades, with Jagger conceding that he was greatly influenced by the singer.

The Apollo offers an apt setting for a conversation about Brown. Jagger first saw Brown perform here in the early '60s, seated next to a woman smoking "a big joint." (He didn't partake.) Seated now next to the film's star, Chadwick Boseman, and dressed in a brown fitted jacket, the slight Jagger never breaks a sweat despite the steamy summer temperatures of New York. The 32-year-old Boseman, by contrast, looks like he just played a game of pickup in the Harlem heat, muscles bulging beneath a black T-shirt and running pants. But they seem perfectly in sync when it comes to talking about Brown. They also discuss the challenges of re-creating the legend, where the film deviated from reality and why there's no heir to Mr. Dynamite.

Can you describe the first meeting you two had?

Chadwick Boseman: It was in L.A. in September [2013]. Mick had me over for tea.

Mick Jagger:We talked a lot. We talked generally about how it is to be a performer and more specifically about James. We put on [Brown's] Live at the Apollo album, which was a very big part of my early musical education. I asked Chad how he felt about [playing Brown] because it's a big ask to do this part. There's the nuance of the acting and the changes of age [Boseman plays Brown starting as a teenager and ending in his 60s].

What did you take away from that conversation?

Boseman: You [looking at Jagger] identified the points when James Brown was charming the crowd and directing the band, and sometimes he's teasing the audience with the moments where he’d step away from the microphone and sing. Then you can’t really hear him. There are all these [shifts] just to seduce everyone.

Jagger: That's what every good performer has. Any performer is one person privately and then he's another person when he steps on the stage. And James Brown, of course, was that. If you’re an actor playing this role, that's another layer in your interpretation.

How closely did the film’s T.A.M.I. Show sequence align with reality?

Jagger: A lot of poetic license was taken. It happened kind of like that, but not exactly. I would have liked to have done it as it actually happened, but we couldn't that do for various reasons, mostly due to money. The true part of it is James was very miffed about not being the top of the bill. In real life, they asked me to go and chill him out because I’d already met him and already talked to him. They thought I’d be a good person because they didn't want to do the dirty work. So, they asked me to try and go chill him out, which I did to a certain extent. But, of course, he wanted to show the real thing that we show in the film -- he wanted to go out there and kill, you know. And that probably made for a better performance than normal. He talked about that a lot afterwards and it meant a lot to him. And I think it was probably the first time that his entire show had been put down on film like that. That’s important for you as an artist.

Mick, you knew James Brown. What was he like as a person and artist?

Jagger: He was always so very nice to me, polite to me, respectful. Even when I was very young, he didn't treat me like I was a whippersnapper. He always was encouraging to me. I watched him a lot, and I think he inspired me and I learned a lot from him. Not like doing imitations but just learning his general attitudes and the way he worked. I'll always admire him for what he did.

Chadwick, unlike Mick, you didn't know James Brown. But what was your experience with him prior to this movie?

Boseman: I don't ever remember there not being a James Brown in my life. I was probably listening to James Brown in the crib [Boseman grew up in South Carolina]. My aunt listened to him. My mom and dad. There was always James Brown all day.

Do you think James Brown has an heir?

Jagger: Chad is. [laughs] But no, I don't think so. But this is another time, and things are different. There's lots of people obviously that are very influenced by him.

Boseman: The whole idea of the businessman and the artist. You see that in hip-hop now.

Jagger: I mean, you look at Jay Z, for instance, and Puff Daddy. They’re very much into that business thing. I was never that interested in business, to be honest. I do the minimal amount of business as possible because I’m not actually interested in it as a thing. But some people are interested in it, and there’s nothing wrong with that. They want to make deals for the deal’s sake. James Brown was definitely a progenitor of that kind of businessman/performer. Before James there was a dearth of people from the African-American community who were entrepreneurs. You weren’t expected to be an entrepreneur. If you were an entertainer, you were just paid and were told what to do and where to go. And you just did it. He was one of the first people that said, “No. I want to take control.”

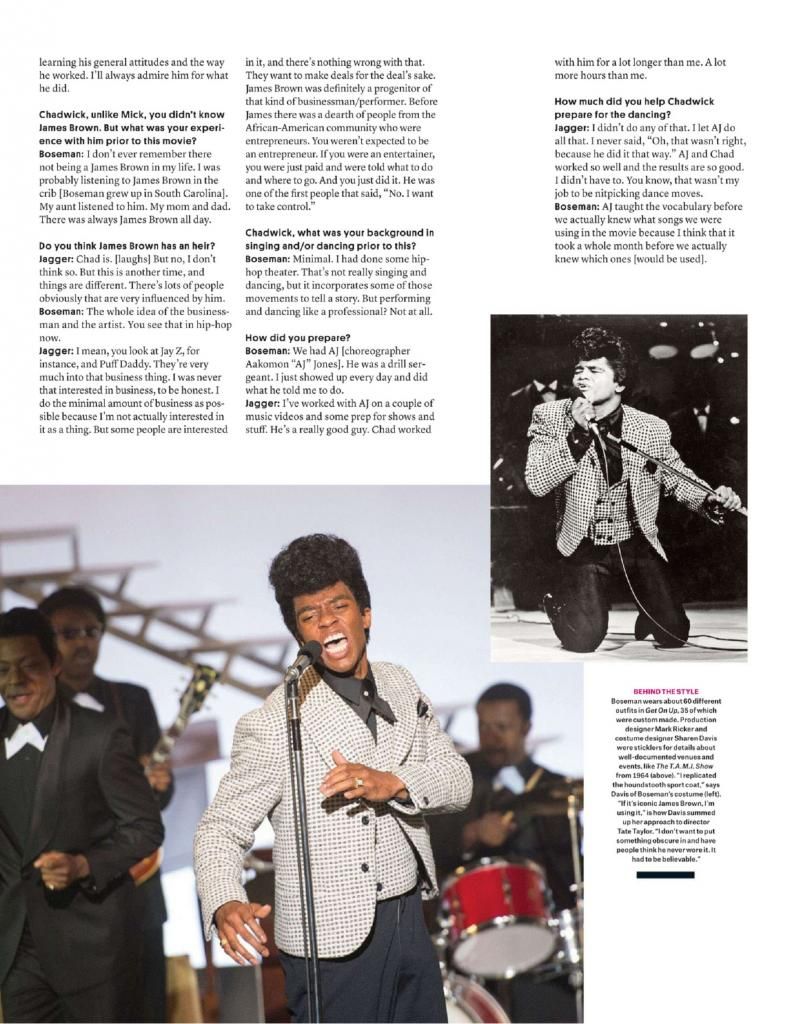

Chadwick, what was your background in singing and/or dancing prior to this?

Boseman: Minimal. I had done some hip-hop theater. That’s not really singing and dancing, but it incorporates some of those movements to tell a story. But performing and dancing like a professional? Not at all.

How did you prepare?

Boseman: We had AJ [choreographer Aakomon "AJ" Jones]. He was a drill sergeant. I just showed up every day and did what he told me to do.

Jagger: I've worked with AJ on a couple of music videos and some prep for shows and stuff. He’s a really good guy. Chad worked with him for a lot longer than me. A lot more hours than me.

How much did you help Chadwick prepare for the dancing?

Jagger: I didn’t do any of that. I let AJ do all that. I never said, "Oh, that wasn't right, because he did it that way." AJ and Chad worked so well and the results are so good. I didn't have to. You know, that wasn't my job to be nitpicking dance moves.

Boseman: AJ taught the vocabulary before we actually knew what songs we were using in the movie because I think that it took a whole month before we actually knew which ones [would be used].

How did you choose the songs?

Jagger: We wanted the songs to fit in with the narrative. There are a lot of songs to choose from. We kept changing the songs.

Mick, you have a well-documented fascination with African-American culture. Was James Brown your entry point?

Jagger: No, definitely not. When I was much younger, like 11 and 12 years old, we used to have people come to England and play, like blues singers Big Bill Broonzy and gospel singers like Sister Rosetta Tharpe. My mother was very fond of these performers, too. She would say, "Sister Rosetta Tharpe's on the TV. Come and watch." That was my intro -- TV. When I was a little older, I used to be able to go and see these shows that came. Like there was The Caravans. There was folk blues, a group of 10, 12 performers, and they would play in London, and I would go and see them in the theater. I didn't come across James Brown until I was a little bit older because he didn't come [to London]. I was aware of his records, but I was more of a blues, a country blues person. But I liked everything, like Elvis and Buddy Holly. I liked country music, like George Jones.

There have been grumblings that this movie should have been directed by a black director. Thoughts?

Boseman: When I look at this situation, I ask, "Who could have done this with the amount of money that was the budget that we had?" I look at the work that Tate [Taylor] put into it. I look at how he fought for certain things and how he brought out who the man was. He developed a relationship with the family. I think there's no color in that. The people that are grumbling have no idea of the nuances of that and the details of this specific situation.

Jagger: I would hate to say as a non-African-American person that it would be wrong for a black person to direct white people in a movie. Wouldn't that be awful of me to say that? The only sympathizing thing I might say for people that want to [grumble] is that a filmmaker should have an understanding for the place where the people you're portraying are coming from. If I was going to make a movie about Korean people, it would be stupid of me just to make it with no understanding and sympathy. I agree with all that Chad says [about Taylor].

How involved was the family?

Boseman: They were involved every day. They read the scripts beforehand. They were asked their opinions about all the drafts of the shooting. We interviewed different people in the family, different sides of the family.

Chadwick, how did you deal with the huge age range you play, from a teenager to his 60s? Did you shoot linearly?

Boseman: No. Some days, I was 63 in the morning and 17 after lunch, and then 35.

Jagger: I would turn around and go, "Wait a minute. He looks different now."

Despite re-creating everything from the Apollo Theater to Vietnam, you kept the budget relatively low, at around $30 million. How were you able to do that?

Jagger: We shot it in 49 days. [laughs]

Boseman: We could have shot for a whole other month.

As a producer, how important would it be to win an Oscar? Is that something you care about?

Jagger: I think everyone in the movie industry wants to win an Oscar. I don't think that's why you make movies. But winning an Oscar is not just about making a great movie, unfortunately. It's also having a good Oscar campaign. It's not something to think about right this second.

How is the HBO rock'n'roll series going with Martin Scorsese?

Jagger: It's going well. I was down there last night on the set on Crosby Street. It looks really interesting. Some great shots we saw last night and some great camera movements and like some really amazing stuff. It should be amazing.

Mick, you have another biopic in the works with the Elvis story, Last Train to Memphis, at Fox 2000. What is its status?

Jagger: We've got a new script and it’s moving forward. But no actor yet.

Speaking of musical biopics, will there ever be a Stones one?

Jagger: Who knows? Who knows, my dear?

[www.billboard.com]

Jagger's James Brown: Mick Jagger & Chadwick Boseman Photo Shoot > [www.billboard.com]

By Tatiana Siegel | July 25, 2014

Joe Pugliese

What's it like when Mick makes you his movie's leading man? The legendary rocker-turned-Hollywood producer and 'Get On Up' star Chadwick Boseman reveal what went on behind the scenes to bring James Brown back to life.

"It's good to be back," says Mick Jagger, sweeping a hand across the grand view in front of him at the historic Apollo Theater in Harlem. The Rolling Stones frontman, who moonlights as an increasingly busy Hollywood producer, is here to discuss Universal's James Brown biopic Get On Up, two days before the film premieres at the same venue. It has been years since Jagger, who turns 71 on July 26, last visited the majestic Apollo. He can’t recall exactly when.

"I came a lot like in the ’80s, and then it was closed for repairs a lot," he says. It's clear that Jagger is feeling slightly nostalgic. "Over the years, I've been in and out of here quite a few times."

For Jagger, Get On Up -- directed by Tate Taylor of The Help and opening Aug. 1 -- proved to be a formidable journey, taking eight years to reach the big screen. The project has been around longer than that, though — at least 12 years. Producer Brian Grazer, fresh off a best picture Oscar win for A Beautiful Mind, signed a deal with Brown in 2002 to secure the Godfather of Soul's life rights. A parade of directors like Spike Lee and actors including Eddie Murphy and Chris Tucker floated in and out of the Brown orbit, with things becoming more complicated after the three-time Grammy-winning icon died in 2006, with his estate in disarray (a court battle between his widow and his children continues to this day, with the South Carolina Supreme Court saying the estate has an undetermined value between $5 million and more than $100 million).

Jagger began working on the project when Peter Afterman -- a music supervisor since the mid-'80s on films from The Big Easy to Juno who now runs the Brown estate — approached him about doing a documentary on the late singer. (Jagger wound up enlisting for both a narrative feature and an upcoming doc directed by Alex Gibney.) After all, Jagger and Brown are forever entwined in music history after appearing on the same bill for the 1964 concert film The T.A.M.I. Show — the Stones were top-billed, much to the dismay of Brown, who famously upstaged the young British rockers in a legendary 18-minute performance sequence. (Michael Jackson, among others, was obsessed with the footage.) Still, the two remained friends for decades, with Jagger conceding that he was greatly influenced by the singer.

The Apollo offers an apt setting for a conversation about Brown. Jagger first saw Brown perform here in the early '60s, seated next to a woman smoking "a big joint." (He didn't partake.) Seated now next to the film's star, Chadwick Boseman, and dressed in a brown fitted jacket, the slight Jagger never breaks a sweat despite the steamy summer temperatures of New York. The 32-year-old Boseman, by contrast, looks like he just played a game of pickup in the Harlem heat, muscles bulging beneath a black T-shirt and running pants. But they seem perfectly in sync when it comes to talking about Brown. They also discuss the challenges of re-creating the legend, where the film deviated from reality and why there's no heir to Mr. Dynamite.

Can you describe the first meeting you two had?

Chadwick Boseman: It was in L.A. in September [2013]. Mick had me over for tea.

Mick Jagger:We talked a lot. We talked generally about how it is to be a performer and more specifically about James. We put on [Brown's] Live at the Apollo album, which was a very big part of my early musical education. I asked Chad how he felt about [playing Brown] because it's a big ask to do this part. There's the nuance of the acting and the changes of age [Boseman plays Brown starting as a teenager and ending in his 60s].

What did you take away from that conversation?

Boseman: You [looking at Jagger] identified the points when James Brown was charming the crowd and directing the band, and sometimes he's teasing the audience with the moments where he’d step away from the microphone and sing. Then you can’t really hear him. There are all these [shifts] just to seduce everyone.

Jagger: That's what every good performer has. Any performer is one person privately and then he's another person when he steps on the stage. And James Brown, of course, was that. If you’re an actor playing this role, that's another layer in your interpretation.

How closely did the film’s T.A.M.I. Show sequence align with reality?

Jagger: A lot of poetic license was taken. It happened kind of like that, but not exactly. I would have liked to have done it as it actually happened, but we couldn't that do for various reasons, mostly due to money. The true part of it is James was very miffed about not being the top of the bill. In real life, they asked me to go and chill him out because I’d already met him and already talked to him. They thought I’d be a good person because they didn't want to do the dirty work. So, they asked me to try and go chill him out, which I did to a certain extent. But, of course, he wanted to show the real thing that we show in the film -- he wanted to go out there and kill, you know. And that probably made for a better performance than normal. He talked about that a lot afterwards and it meant a lot to him. And I think it was probably the first time that his entire show had been put down on film like that. That’s important for you as an artist.

Mick, you knew James Brown. What was he like as a person and artist?

Jagger: He was always so very nice to me, polite to me, respectful. Even when I was very young, he didn't treat me like I was a whippersnapper. He always was encouraging to me. I watched him a lot, and I think he inspired me and I learned a lot from him. Not like doing imitations but just learning his general attitudes and the way he worked. I'll always admire him for what he did.

Chadwick, unlike Mick, you didn't know James Brown. But what was your experience with him prior to this movie?

Boseman: I don't ever remember there not being a James Brown in my life. I was probably listening to James Brown in the crib [Boseman grew up in South Carolina]. My aunt listened to him. My mom and dad. There was always James Brown all day.

Do you think James Brown has an heir?

Jagger: Chad is. [laughs] But no, I don't think so. But this is another time, and things are different. There's lots of people obviously that are very influenced by him.

Boseman: The whole idea of the businessman and the artist. You see that in hip-hop now.

Jagger: I mean, you look at Jay Z, for instance, and Puff Daddy. They’re very much into that business thing. I was never that interested in business, to be honest. I do the minimal amount of business as possible because I’m not actually interested in it as a thing. But some people are interested in it, and there’s nothing wrong with that. They want to make deals for the deal’s sake. James Brown was definitely a progenitor of that kind of businessman/performer. Before James there was a dearth of people from the African-American community who were entrepreneurs. You weren’t expected to be an entrepreneur. If you were an entertainer, you were just paid and were told what to do and where to go. And you just did it. He was one of the first people that said, “No. I want to take control.”

Chadwick, what was your background in singing and/or dancing prior to this?

Boseman: Minimal. I had done some hip-hop theater. That’s not really singing and dancing, but it incorporates some of those movements to tell a story. But performing and dancing like a professional? Not at all.

How did you prepare?

Boseman: We had AJ [choreographer Aakomon "AJ" Jones]. He was a drill sergeant. I just showed up every day and did what he told me to do.

Jagger: I've worked with AJ on a couple of music videos and some prep for shows and stuff. He’s a really good guy. Chad worked with him for a lot longer than me. A lot more hours than me.

How much did you help Chadwick prepare for the dancing?

Jagger: I didn’t do any of that. I let AJ do all that. I never said, "Oh, that wasn't right, because he did it that way." AJ and Chad worked so well and the results are so good. I didn't have to. You know, that wasn't my job to be nitpicking dance moves.

Boseman: AJ taught the vocabulary before we actually knew what songs we were using in the movie because I think that it took a whole month before we actually knew which ones [would be used].

How did you choose the songs?

Jagger: We wanted the songs to fit in with the narrative. There are a lot of songs to choose from. We kept changing the songs.

Mick, you have a well-documented fascination with African-American culture. Was James Brown your entry point?

Jagger: No, definitely not. When I was much younger, like 11 and 12 years old, we used to have people come to England and play, like blues singers Big Bill Broonzy and gospel singers like Sister Rosetta Tharpe. My mother was very fond of these performers, too. She would say, "Sister Rosetta Tharpe's on the TV. Come and watch." That was my intro -- TV. When I was a little older, I used to be able to go and see these shows that came. Like there was The Caravans. There was folk blues, a group of 10, 12 performers, and they would play in London, and I would go and see them in the theater. I didn't come across James Brown until I was a little bit older because he didn't come [to London]. I was aware of his records, but I was more of a blues, a country blues person. But I liked everything, like Elvis and Buddy Holly. I liked country music, like George Jones.

There have been grumblings that this movie should have been directed by a black director. Thoughts?

Boseman: When I look at this situation, I ask, "Who could have done this with the amount of money that was the budget that we had?" I look at the work that Tate [Taylor] put into it. I look at how he fought for certain things and how he brought out who the man was. He developed a relationship with the family. I think there's no color in that. The people that are grumbling have no idea of the nuances of that and the details of this specific situation.

Jagger: I would hate to say as a non-African-American person that it would be wrong for a black person to direct white people in a movie. Wouldn't that be awful of me to say that? The only sympathizing thing I might say for people that want to [grumble] is that a filmmaker should have an understanding for the place where the people you're portraying are coming from. If I was going to make a movie about Korean people, it would be stupid of me just to make it with no understanding and sympathy. I agree with all that Chad says [about Taylor].

How involved was the family?

Boseman: They were involved every day. They read the scripts beforehand. They were asked their opinions about all the drafts of the shooting. We interviewed different people in the family, different sides of the family.

Chadwick, how did you deal with the huge age range you play, from a teenager to his 60s? Did you shoot linearly?

Boseman: No. Some days, I was 63 in the morning and 17 after lunch, and then 35.

Jagger: I would turn around and go, "Wait a minute. He looks different now."

Despite re-creating everything from the Apollo Theater to Vietnam, you kept the budget relatively low, at around $30 million. How were you able to do that?

Jagger: We shot it in 49 days. [laughs]

Boseman: We could have shot for a whole other month.

As a producer, how important would it be to win an Oscar? Is that something you care about?

Jagger: I think everyone in the movie industry wants to win an Oscar. I don't think that's why you make movies. But winning an Oscar is not just about making a great movie, unfortunately. It's also having a good Oscar campaign. It's not something to think about right this second.

How is the HBO rock'n'roll series going with Martin Scorsese?

Jagger: It's going well. I was down there last night on the set on Crosby Street. It looks really interesting. Some great shots we saw last night and some great camera movements and like some really amazing stuff. It should be amazing.

Mick, you have another biopic in the works with the Elvis story, Last Train to Memphis, at Fox 2000. What is its status?

Jagger: We've got a new script and it’s moving forward. But no actor yet.

Speaking of musical biopics, will there ever be a Stones one?

Jagger: Who knows? Who knows, my dear?

[www.billboard.com]

Jagger's James Brown: Mick Jagger & Chadwick Boseman Photo Shoot > [www.billboard.com]

Re: Mick: 'Get On Up' film & HBO TV series

Posted by:

crawdaddy

()

Date: July 25, 2014 21:07

Thanks bbj.

Another great article.

Another great article.

Mick & Chadwick Boseman - Billboard, August 2

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: July 26, 2014 00:09

Not-so-great crop of one of the pictures in Joe Pugliese's Billboard photoset. The full image:

A little less stoic:

[www.billboard.com]

A little less stoic:

[www.billboard.com]

Re: Mick: 'Get On Up' film & HBO TV series

Posted by:

Dreamer

()

Date: July 26, 2014 00:44

Great reads & pics proudmary & bbj: thanks!

Re: Mick: 'Get On Up' film & HBO TV series

Posted by:

DandelionPowderman

()

Date: July 26, 2014 00:48

Re: Mick: 'Get On Up' film & HBO TV series

Posted by:

Stoneage

()

Date: July 26, 2014 02:15

Imagine all the time you have on your hand when you don't write new RS songs or produce new RS albums...

Re: Mick: 'Get On Up' film & HBO TV series

Posted by:

alieb

()

Date: July 26, 2014 03:08

Quote

Stoneage

Imagine all the time you have on your hand when you don't write new RS songs or produce new RS albums...

on the other hand, he could be spending his spare time exclusively playing cricket and/or socializing and not working hard to make exciting new products for public consumption...

Re: Mick & Chadwick Boseman - Billboard, August 2

Posted by:

with sssoul

()

Date: July 26, 2014 16:38

Quote

bye bye johnny

The full image:

I love that shot - thanks for posting the whole thing, bbj

'Get On Up'

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: July 28, 2014 17:23

Mick Jagger: James Brown 'gave his best in every show'

Edna Gundersen, USA TODAY July 27, 2014

(Photo: Dave Allocca, Starpix)

Mick Jagger copped plenty of dance moves from James Brown, and the similarities don't end there.

"James was definitely one of those guys with super drive and energy," Jagger says of the late Godfather of Soul. "He stayed in shape all the time. He never left the audience bored. He involved the audience and kept them amused and entertained. He gave his best in every show."

Jagger, who turned 71 Saturday, could be talking about himself. The Rolling Stones singer, on a break from the band's 14 On Fire world tour, is promoting the Brown biopic Get On Up, which he produced through his Jagged Films. It opens Friday.

Early in his career, the singer was inspired by Brown's charisma, footwork and vocal chops. When the film project hit his doorstep eight years ago, Jagger jumped.

Producer Brian Grazer had secured the rights to Brown's life in 2002, "but the project never got anywhere for various reasons," Jagger says. "James didn't like this or that, Brian had to keep extending the rights, and it just ran out of steam. When James died, it got more complicated because people in the estate were arguing amongst themselves."

His widow and children continue to litigate over the fortune Brown left when he died on Christmas Day in 2006. Estate manager Peter Afterman asked pal Jagger if he wanted to produce a Brown documentary. Assured that Afterman had acquired full music rights ("You need one person administering them, not 20" ), Jagger agreed, then suggested a feature.

Next, Jagger tracked down an early script by Jez and John-Henry Butterworth and partnered with Grazer.

"We had to go to the studio to get the money," Jagger says. "These kind of biopics have a mixed run at the box office. Once Universal made up its mind, they got behind it. It went quickly from there."

The $30 million film, directed by Tate Taylor and starring Chadwick Boseman, was shot in 49 days, and Jagger was thrilled with the results: a music-driven nonlinear depiction of Brown's ascent from poverty and abuse to global acclaim.

"It's not so unconventional that it puts you off, and it's not a whitewash but not too negative," he says. "And the music really sounds great."

It always has, says Jagger, whose first exposure to Brown was such early singles as 1958's Try Me and 1960's Think (covered live in recent years by the Stones), then 1963 album Live at the Apollo.

"I listened to it intently," Jagger says. "You can hear that he's a great performer, and I was picturing how he would dance. Then I went to see him at the Apollo and I was blown away. I was impressed by how hard he worked and how he had the audience in the palm of his hand. That was a learning experience for me."

The two struck up a friendship after one of Brown's shows at the fabled Harlem theater.

"He was always very nice, very generous, but he talked about business a lot and I wasn't that interested in it," says Jagger, who considers Brown a forerunner to such contemporary black music moguls as Jay Z and Puffy Combs.

Get On Up revisits the milestone Apollo gig, the 1968 Boston Garden concert the night after Martin Luther King's death and 1964's legendary T.A.M.I. Show in Santa Monica, where Brown upstaged the Stones after complaining about his lower spot on the bill.

"That's a little poetic license," Jagger says of a scene showing the nervous British rockers in the wings as Soul Brother No. 1 steals the show. Jagger says he didn't watch Brown, but he does recall Brown stewing about not headlining. Promoters, uneasy about approaching the perturbed singer, dispatched Jagger to appease him.

"James was very competitive, and I'm sure he wanted to put on the best show," Jagger says. "It was an odd project, a rock 'n' roll film with a very eclectic cast. The Motown acts already had No. 1 singles. The Rolling Stones were big in California. They had The Supremes, Marvin Gaye, Lesley Gore. For James, it was a non-chitlin' circuit, mainstream breakthrough, very important for him."

For decades, Jagger was well-versed in Brown's catalog and its impact on all genres. He was less familiar with Brown's early life until he began digging.

"I never knew much about the abject poverty and abandonment or life in the backwoods of Georgia," he says. "That was like another country. When I first came to the States, I'd go to New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, and middle-class people you rubbed shoulders with in those towns didn't know that other America existed."

Jagger also produced upcoming documentary Mr. Dynamite: James Brown and the Power of Soul, directed by Alex Gibney. The HBO series Rock and Roll, his music-business drama with partners Martin Scorsese and Terence Winter, is in production. And Elvis Presley biopic Last Train to Memphis gets under way soon.

Not on Jagger's to-do list: a film version of his own storied career.

"There's been some garbage script floating around," he grouses. "It's of no literary merit. Most people that write this stuff are useless. Probably someone will do one someday, who knows."

[www.usatoday.com]

_____

From the movie soundtrack, out July 29 - previously unreleased live version of "It's a Man's Man's Man's World" > [w.soundcloud.com]

[www.rollingstone.com]

Edna Gundersen, USA TODAY July 27, 2014

(Photo: Dave Allocca, Starpix)

Mick Jagger copped plenty of dance moves from James Brown, and the similarities don't end there.

"James was definitely one of those guys with super drive and energy," Jagger says of the late Godfather of Soul. "He stayed in shape all the time. He never left the audience bored. He involved the audience and kept them amused and entertained. He gave his best in every show."

Jagger, who turned 71 Saturday, could be talking about himself. The Rolling Stones singer, on a break from the band's 14 On Fire world tour, is promoting the Brown biopic Get On Up, which he produced through his Jagged Films. It opens Friday.

Early in his career, the singer was inspired by Brown's charisma, footwork and vocal chops. When the film project hit his doorstep eight years ago, Jagger jumped.

Producer Brian Grazer had secured the rights to Brown's life in 2002, "but the project never got anywhere for various reasons," Jagger says. "James didn't like this or that, Brian had to keep extending the rights, and it just ran out of steam. When James died, it got more complicated because people in the estate were arguing amongst themselves."

His widow and children continue to litigate over the fortune Brown left when he died on Christmas Day in 2006. Estate manager Peter Afterman asked pal Jagger if he wanted to produce a Brown documentary. Assured that Afterman had acquired full music rights ("You need one person administering them, not 20" ), Jagger agreed, then suggested a feature.

Next, Jagger tracked down an early script by Jez and John-Henry Butterworth and partnered with Grazer.

"We had to go to the studio to get the money," Jagger says. "These kind of biopics have a mixed run at the box office. Once Universal made up its mind, they got behind it. It went quickly from there."

The $30 million film, directed by Tate Taylor and starring Chadwick Boseman, was shot in 49 days, and Jagger was thrilled with the results: a music-driven nonlinear depiction of Brown's ascent from poverty and abuse to global acclaim.

"It's not so unconventional that it puts you off, and it's not a whitewash but not too negative," he says. "And the music really sounds great."

It always has, says Jagger, whose first exposure to Brown was such early singles as 1958's Try Me and 1960's Think (covered live in recent years by the Stones), then 1963 album Live at the Apollo.

"I listened to it intently," Jagger says. "You can hear that he's a great performer, and I was picturing how he would dance. Then I went to see him at the Apollo and I was blown away. I was impressed by how hard he worked and how he had the audience in the palm of his hand. That was a learning experience for me."

The two struck up a friendship after one of Brown's shows at the fabled Harlem theater.

"He was always very nice, very generous, but he talked about business a lot and I wasn't that interested in it," says Jagger, who considers Brown a forerunner to such contemporary black music moguls as Jay Z and Puffy Combs.

Get On Up revisits the milestone Apollo gig, the 1968 Boston Garden concert the night after Martin Luther King's death and 1964's legendary T.A.M.I. Show in Santa Monica, where Brown upstaged the Stones after complaining about his lower spot on the bill.

"That's a little poetic license," Jagger says of a scene showing the nervous British rockers in the wings as Soul Brother No. 1 steals the show. Jagger says he didn't watch Brown, but he does recall Brown stewing about not headlining. Promoters, uneasy about approaching the perturbed singer, dispatched Jagger to appease him.

"James was very competitive, and I'm sure he wanted to put on the best show," Jagger says. "It was an odd project, a rock 'n' roll film with a very eclectic cast. The Motown acts already had No. 1 singles. The Rolling Stones were big in California. They had The Supremes, Marvin Gaye, Lesley Gore. For James, it was a non-chitlin' circuit, mainstream breakthrough, very important for him."

For decades, Jagger was well-versed in Brown's catalog and its impact on all genres. He was less familiar with Brown's early life until he began digging.

"I never knew much about the abject poverty and abandonment or life in the backwoods of Georgia," he says. "That was like another country. When I first came to the States, I'd go to New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, and middle-class people you rubbed shoulders with in those towns didn't know that other America existed."

Jagger also produced upcoming documentary Mr. Dynamite: James Brown and the Power of Soul, directed by Alex Gibney. The HBO series Rock and Roll, his music-business drama with partners Martin Scorsese and Terence Winter, is in production. And Elvis Presley biopic Last Train to Memphis gets under way soon.

Not on Jagger's to-do list: a film version of his own storied career.

"There's been some garbage script floating around," he grouses. "It's of no literary merit. Most people that write this stuff are useless. Probably someone will do one someday, who knows."

[www.usatoday.com]

_____

From the movie soundtrack, out July 29 - previously unreleased live version of "It's a Man's Man's Man's World" > [w.soundcloud.com]

[www.rollingstone.com]

Re: Mick: 'Get On Up' film & HBO TV series

Posted by:

duke richardson

()

Date: July 28, 2014 17:35

Not on Jagger's to-do list: a film version of his own storied career.

then he goes on to say none of whats been written is any good.

if a credible script got written by implication he would consider it.

I think it would be a great story, especially if told by Stu. model the script that way, the way he would have told it, straight up. have it tell the early Stones' struggle, Stu's involvement was so crucial, he could then say what happened exactly when he got relegated to the behind the scenes role as their career took off. A lot of interesting club and ballroom gigs would be staged. A lot of the Brian- Keith- Mick relationship, would be told by Stu who would pull no punches.

of course I mean an imagined telling from Stu's point of view..

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2014-07-28 17:53 by duke richardson.

then he goes on to say none of whats been written is any good.

if a credible script got written by implication he would consider it.

I think it would be a great story, especially if told by Stu. model the script that way, the way he would have told it, straight up. have it tell the early Stones' struggle, Stu's involvement was so crucial, he could then say what happened exactly when he got relegated to the behind the scenes role as their career took off. A lot of interesting club and ballroom gigs would be staged. A lot of the Brian- Keith- Mick relationship, would be told by Stu who would pull no punches.

of course I mean an imagined telling from Stu's point of view..

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2014-07-28 17:53 by duke richardson.

'Get On Up'

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: July 28, 2014 17:55

Q & A from the July 17 screening for Academy members:

Re: 'Get On Up'

Posted by:

proudmary

()

Date: July 29, 2014 22:27

Why Did Mick Jagger Produce The James Brown Movie, 'Get On Up'? Let Him Tell You

Mick Jagger has been a James Brown fan for actual decades. The Rolling Stones lead singer, who turned 71 on Sunday, has admitted he copied many of Brown's dance moves on stage. As the men rose to prominence as two of the biggest singers of the 1960s, they even became acquaintances. It was a relationship that lasted until Brown's death in 2006.

"I saw him at a show in Cleveland. I can't remember when, but we were both there together," Jagger told HuffPost Entertainment when asked about the last time he saw Brown alive. "I went to see his show, and he came to see me. We had a good time."

For Jagger, his connection to Brown has only increased in the eight years since the pioneering singer died. Peter Afterman, Brown's estate manager and Jagger's long-time friend, asked the Rolling Stones frontman if he wanted to make a documentary on Brown's life after securing music rights to Brown's catalog of hit songs. Jagger thought to take it one step further: a feature film about Brown that could work in concert with documentary. It was then that he connected with producer Brian Grazer, who had been working on a Brown movie himself for a decade with little triumph. Using a script written by Jez and John-Henry Butterworth, Jagger and Grazer put together "Get On Up," an unconventional biography about Brown that jumps through the singer's life, from his troubled upbringing in Georgia to his incredible career as a performer to his numerous issues with the law. (Brown was arrested multiple times on domestic violence charges and also spent time in prison for other offenses, including a three-year stint after leading police on a high-speed chase in 1988.)

Starring Chadwick Boseman as Brown and directed by Tate Taylor, "Get On Up" hopes to capitalize on audiences who helped make "Lee Daniels' The Butler" and Taylor's previous film, Best Picture-nominee "The Help," surprise box office hits in the month of August. For his part, Jagger has everything in his power to make the film a success: In addition to being a hands-on producer for "Get On Up" during production, Jagger has promoted the film on the "Today" show and in interviews with TIME magazine, Billboard, USA Today and The Huffington Post. We spoke to Jagger about his involvement in "Get On Up" at the world famous Apollo Theater in New York on a hazy, hot and humid Saturday afternoon in July. An edited transcript of our conversation is below.

You were producing the Alex Gibney documentary, "Mr. Dynamite: James Brown and the Power of Soul," and, as the story goes in the press notes, woke up one day and thought a feature on Brown would be great too. Why?

It's just a different animal, isn't it? Obviously I thought of "Ray." I thought "Ray" was a great movie. I loved that movie and people loved that movie. But I thought, in a way, that James Brown's life story and his onstage persona was more interesting. The onstage performances are more vivid and alive than in Ray's story. As much as we love Ray Charles, and he's one of my favorite singers, but I mean, when I thought about it, I thought, "Wow, if you could make a movie like that [with Ray Charles], we can certainly do a movie about someone like James Brown." But without copying "Ray" in any way, so why not make a feature of it too? And we can do the documentary, too. They can both be fantastic.

You've discussed how James Brown influenced you. Watching the movie, I couldn't help but think of how we can see parts of James Brown in singers like David Lee Roth and Axl Rose and also modern hip-hop artists like Kanye West and Jay Z. Do you think people even realize how influential Brown was across all genres of music?

Well, probably not. Why would they? But he was definitely a role model on many levels. He's a role model as a guy who comes out on stage and really works his butt off. He always gave his best. He came out and did it. I never thought, "I want to be like that!" But obviously that rubs off on you. The other person I toured with was Little Richard. Every night he went out there -- didn't matter who the audience was, whether they were good, bad or indifferent -- and he just worked it. That rubs off on you. These are guys who were just always working it. So that's the way you want to be. On the other level, James Brown wanted to be in control of his own destiny. This movie is about someone who wants to be in control of their career and their life, especially when they came from a place where they weren't in control or they had very little to start with.

The movie depicts the infamous T.A.M.I. concert, and shows a screen version of The Rolling Stones watching Brown perform. How familiar were you with Brown before that show?

Very familiar. I had everything. I had all his music. I had seen his music here at the Apollo. I talked to him. I hung out with him.

How much influence did you have on who was cast as a Mick Jagger for that scene?

Not much, in the end. I was somewhere far away. I don't want to talk about it really. How can I talk about it without sounding ... there was a little bit of poetic license in that scene. In the end the scene works. It's a fun scene. It wasn't really what happened, but it works well.

As a producer was there one moment that you really fought to keep in the finished film?

I can't really remember. My thing was, I wanted you, the audience, to be pulling for James. Sometimes when I read the script, I felt there was some feeling that you ... I was really saying, "I'm not pulling for this guy enough." It was quite simple really: It was just a question of juxtaposition of a few scenes. It wasn't really taking things out, it was where things were in the story. It's just where you put the accentuation. It doesn't matter how bad he is or how good he is, you want to see both sides of a character. But nevertheless, you do want to be pulling for him.

You obviously don't need to be a producer. Why do you do it?

I quite enjoy doing it. It's a different discipline, but it has a lot of things that are the same [as leading the Rolling Stones]: managing large groups of people, making sure they get on with a common goal. But you've also got a lot of competing parties and you have problems to solve and so on. I also like the literary part of it, which I don't really get to do that much. I like the scripts. I like solving the puzzles. I kind of enjoy the dealmaking. I mean, as long as it doesn't go on forever. It's a lot of moving parts! As long as it doesn't take all my time, because I like to do creative things in other ways, it's a great thing. It's still a creative thing, it's not a business only thing. So it depends which route you take. Being a producer can mean many things. For this particular movie, it was quite interesting because it did have a good literary beginning. Other movies you're presented with a script and there is very little you can say. It's done. It could even be cast. You still get the same credit. With this, it was a much longer process.

You weren't just a rubber stamp of approval.

I'm not really interested in doing that. I don't mind doing that, you know, if it's a project you really love.

With this film and the documentary, you've become the de facto caretaker of James Brown's legacy for a generation of young viewers. Do you think about who will do that for you and the Rolling Stones?

Not really. I don't think about that much [laughs]. I always get asked about it!

With that in mind, did you feel any pressure to make sure James Brown's legacy was shown in a way that was true to him?

Yeah, I want it to be true to him. I think he's a wonderful artist and I didn't want it to be over-glamorized or too de-glamorized and sleazy. In making the documentary, it was the same thing. By shading and nuancing, you can destroy someone's reputation. In the documentary, for instance, it would be very easy to accentuate the negative side -- which everyone has in their life -- and that would be a mean thing to do. What I tried to do in both these films is to show not only the creative and other side, but to show him as a complete person as much as possible. But still really leave people with an uplifting feeling, which I think is a correct thing to do for an artist of his status.

How did you decide on Tate Taylor as director?

Brian and I, once we decided to partner up but before we had a deal, we decided to look for directors. We looked at lots of directors, and Tate was on the top of our list of people. We thought that even though Tate was relatively inexperienced, he did have experience with doing "The Help," which we liked. It was a bit of a leap of faith with Tate because he hadn't done a lot. But he convinced us that he could do this and he had boundless enthusiasm and energy and vitality to push the project through, especially for the limited amount of money that we had to make it. We decided that Tate could do it. I think we were vindicated at the end.

When did you realize it was the right decision?

When you start seeing the first assembly cut, after the first couple of weeks. You know, "Okay, I think it's working. We're going to keep going!"

Tate's going to be forever connected with James Brown, and I wanted to ask you about your connection with Martin Scorsese. Do you have a favorite scene from his movies set to your music?

I can't remember. He's used "Gimme Shelter" a lot. I'm doing this HBO series with Marty now. I think we're talking about using Stones music in that. Some of it. But, yeah he has a really great flare for using music. He was one of the first who used loud rock music, like, in your face. Before, it was sort of in the background, and he lets the music sometimes take over the scene in a really great way.

[www.huffingtonpost.com]

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2014-07-29 22:36 by proudmary.

Mick Jagger has been a James Brown fan for actual decades. The Rolling Stones lead singer, who turned 71 on Sunday, has admitted he copied many of Brown's dance moves on stage. As the men rose to prominence as two of the biggest singers of the 1960s, they even became acquaintances. It was a relationship that lasted until Brown's death in 2006.

"I saw him at a show in Cleveland. I can't remember when, but we were both there together," Jagger told HuffPost Entertainment when asked about the last time he saw Brown alive. "I went to see his show, and he came to see me. We had a good time."

For Jagger, his connection to Brown has only increased in the eight years since the pioneering singer died. Peter Afterman, Brown's estate manager and Jagger's long-time friend, asked the Rolling Stones frontman if he wanted to make a documentary on Brown's life after securing music rights to Brown's catalog of hit songs. Jagger thought to take it one step further: a feature film about Brown that could work in concert with documentary. It was then that he connected with producer Brian Grazer, who had been working on a Brown movie himself for a decade with little triumph. Using a script written by Jez and John-Henry Butterworth, Jagger and Grazer put together "Get On Up," an unconventional biography about Brown that jumps through the singer's life, from his troubled upbringing in Georgia to his incredible career as a performer to his numerous issues with the law. (Brown was arrested multiple times on domestic violence charges and also spent time in prison for other offenses, including a three-year stint after leading police on a high-speed chase in 1988.)

Starring Chadwick Boseman as Brown and directed by Tate Taylor, "Get On Up" hopes to capitalize on audiences who helped make "Lee Daniels' The Butler" and Taylor's previous film, Best Picture-nominee "The Help," surprise box office hits in the month of August. For his part, Jagger has everything in his power to make the film a success: In addition to being a hands-on producer for "Get On Up" during production, Jagger has promoted the film on the "Today" show and in interviews with TIME magazine, Billboard, USA Today and The Huffington Post. We spoke to Jagger about his involvement in "Get On Up" at the world famous Apollo Theater in New York on a hazy, hot and humid Saturday afternoon in July. An edited transcript of our conversation is below.

You were producing the Alex Gibney documentary, "Mr. Dynamite: James Brown and the Power of Soul," and, as the story goes in the press notes, woke up one day and thought a feature on Brown would be great too. Why?

It's just a different animal, isn't it? Obviously I thought of "Ray." I thought "Ray" was a great movie. I loved that movie and people loved that movie. But I thought, in a way, that James Brown's life story and his onstage persona was more interesting. The onstage performances are more vivid and alive than in Ray's story. As much as we love Ray Charles, and he's one of my favorite singers, but I mean, when I thought about it, I thought, "Wow, if you could make a movie like that [with Ray Charles], we can certainly do a movie about someone like James Brown." But without copying "Ray" in any way, so why not make a feature of it too? And we can do the documentary, too. They can both be fantastic.

You've discussed how James Brown influenced you. Watching the movie, I couldn't help but think of how we can see parts of James Brown in singers like David Lee Roth and Axl Rose and also modern hip-hop artists like Kanye West and Jay Z. Do you think people even realize how influential Brown was across all genres of music?

Well, probably not. Why would they? But he was definitely a role model on many levels. He's a role model as a guy who comes out on stage and really works his butt off. He always gave his best. He came out and did it. I never thought, "I want to be like that!" But obviously that rubs off on you. The other person I toured with was Little Richard. Every night he went out there -- didn't matter who the audience was, whether they were good, bad or indifferent -- and he just worked it. That rubs off on you. These are guys who were just always working it. So that's the way you want to be. On the other level, James Brown wanted to be in control of his own destiny. This movie is about someone who wants to be in control of their career and their life, especially when they came from a place where they weren't in control or they had very little to start with.

The movie depicts the infamous T.A.M.I. concert, and shows a screen version of The Rolling Stones watching Brown perform. How familiar were you with Brown before that show?

Very familiar. I had everything. I had all his music. I had seen his music here at the Apollo. I talked to him. I hung out with him.

How much influence did you have on who was cast as a Mick Jagger for that scene?

Not much, in the end. I was somewhere far away. I don't want to talk about it really. How can I talk about it without sounding ... there was a little bit of poetic license in that scene. In the end the scene works. It's a fun scene. It wasn't really what happened, but it works well.

As a producer was there one moment that you really fought to keep in the finished film?

I can't really remember. My thing was, I wanted you, the audience, to be pulling for James. Sometimes when I read the script, I felt there was some feeling that you ... I was really saying, "I'm not pulling for this guy enough." It was quite simple really: It was just a question of juxtaposition of a few scenes. It wasn't really taking things out, it was where things were in the story. It's just where you put the accentuation. It doesn't matter how bad he is or how good he is, you want to see both sides of a character. But nevertheless, you do want to be pulling for him.

You obviously don't need to be a producer. Why do you do it?

I quite enjoy doing it. It's a different discipline, but it has a lot of things that are the same [as leading the Rolling Stones]: managing large groups of people, making sure they get on with a common goal. But you've also got a lot of competing parties and you have problems to solve and so on. I also like the literary part of it, which I don't really get to do that much. I like the scripts. I like solving the puzzles. I kind of enjoy the dealmaking. I mean, as long as it doesn't go on forever. It's a lot of moving parts! As long as it doesn't take all my time, because I like to do creative things in other ways, it's a great thing. It's still a creative thing, it's not a business only thing. So it depends which route you take. Being a producer can mean many things. For this particular movie, it was quite interesting because it did have a good literary beginning. Other movies you're presented with a script and there is very little you can say. It's done. It could even be cast. You still get the same credit. With this, it was a much longer process.

You weren't just a rubber stamp of approval.

I'm not really interested in doing that. I don't mind doing that, you know, if it's a project you really love.

With this film and the documentary, you've become the de facto caretaker of James Brown's legacy for a generation of young viewers. Do you think about who will do that for you and the Rolling Stones?

Not really. I don't think about that much [laughs]. I always get asked about it!

With that in mind, did you feel any pressure to make sure James Brown's legacy was shown in a way that was true to him?

Yeah, I want it to be true to him. I think he's a wonderful artist and I didn't want it to be over-glamorized or too de-glamorized and sleazy. In making the documentary, it was the same thing. By shading and nuancing, you can destroy someone's reputation. In the documentary, for instance, it would be very easy to accentuate the negative side -- which everyone has in their life -- and that would be a mean thing to do. What I tried to do in both these films is to show not only the creative and other side, but to show him as a complete person as much as possible. But still really leave people with an uplifting feeling, which I think is a correct thing to do for an artist of his status.

How did you decide on Tate Taylor as director?

Brian and I, once we decided to partner up but before we had a deal, we decided to look for directors. We looked at lots of directors, and Tate was on the top of our list of people. We thought that even though Tate was relatively inexperienced, he did have experience with doing "The Help," which we liked. It was a bit of a leap of faith with Tate because he hadn't done a lot. But he convinced us that he could do this and he had boundless enthusiasm and energy and vitality to push the project through, especially for the limited amount of money that we had to make it. We decided that Tate could do it. I think we were vindicated at the end.

When did you realize it was the right decision?

When you start seeing the first assembly cut, after the first couple of weeks. You know, "Okay, I think it's working. We're going to keep going!"

Tate's going to be forever connected with James Brown, and I wanted to ask you about your connection with Martin Scorsese. Do you have a favorite scene from his movies set to your music?

I can't remember. He's used "Gimme Shelter" a lot. I'm doing this HBO series with Marty now. I think we're talking about using Stones music in that. Some of it. But, yeah he has a really great flare for using music. He was one of the first who used loud rock music, like, in your face. Before, it was sort of in the background, and he lets the music sometimes take over the scene in a really great way.

[www.huffingtonpost.com]

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2014-07-29 22:36 by proudmary.

'Get On Up'

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: July 29, 2014 22:58

First Reviews: Chadwick Boseman as James Brown in 'Get On Up'

By Sam Adams

July 28, 2014

Chadwick Boseman as James Brown in "Get On Up"

The dog days of August isn't usually when studios roll out their Oscar contenders. But critics who've gotten an early look at "Get On Up," a biography of James Brown from "The Help's" Tate Taylor, suggest that Chadwick Boseman's performance as the Hardest Working Man in Show Business is one that voters should keep in mind at the end of the year. From its tag line — "Are you read to feel good?" — on down, Universal is selling "Get On Up" as a high-energy hoot rather than an artist-and-his-struggle biopic along the lines of "Ray," but while the early reviews are not without their reservations, they agree the movie manages to pay ample tribute to Brown's unparalleled skills as an entertainer while peeking behind the music as well.

Reviews of "Get On Up"

Scott Foundas, Variety

Perhaps it’s fitting that a movie on a subject as polymorphous as Brown never quite settles on a style or a tone. Rather than following standard chronological-biopic convention, the script by British playwright Jez Butterworth (“Jerusalem”) and his brother John-Henry splinters the narrative into a series of nonlinear fragments, hopscotching across Brown’s life like a rock skimming a turbulent stream. One minute it’s 1964 and Brown — then the lead singer of the Famous Flames — is upstaging the Rolling Stones at the recording of the seminal concert film “The T.A.M.I. Show.” Then, on a dime, it’s back to 1949 and the teenage Brown’s arrest on petty theft charges.

Alonso Duralde, The Wrap

f you thought the recent “Jersey Boys” was stodgy and problematic, here's a music movie that avoids that other film's pitfalls: It places Brown (Chadwick Boseman, in an electrifying performance) into a specific cultural and political context, while also spelling out to a mass audience the musician's innovations as a performer, artist, and businessman. At the same time, “Get on Up” never skids into puff-piece territory; the film shows us that Brown could be a devoted friend but also an insufferable egotist; a loving husband who could, in turn, be abusive to his wives; and a shrewd money manager who also found himself in debt after a series of misguided entrepreneurial decisions.

Tim Grierson, Screen Daily

When "Get On Up" hints at the reasons why Brown behaved this way — for instance, he was abandoned by his parents and forced to live in his aunt’s brothel — the filmmakers don’t oversell their theories as some grand revelation. Instead, because "Get On Up" shifts across decades, pursuing thematic connections as opposed to biographical plot points, the movie feels like a meditation on Brown, not a definitive CliffsNotes on why he’s regarded as one of pop music’s most important artists.

Sheri Linden, Hollywood Reporter

In sync with its subject, director Tate Taylor’s movie, too, can be wearying, especially in the strenuously scrambled chronology of its early sequences. But under the guidance of producer Mick Jagger, it’s that rare musician’s biography with a deep feel for the music. And in Chadwick Boseman, it has a galvanic core, a performance that transcends impersonation and reverberates long after the screen goes dark.

[blogs.indiewire.com]

By Sam Adams

July 28, 2014

Chadwick Boseman as James Brown in "Get On Up"

The dog days of August isn't usually when studios roll out their Oscar contenders. But critics who've gotten an early look at "Get On Up," a biography of James Brown from "The Help's" Tate Taylor, suggest that Chadwick Boseman's performance as the Hardest Working Man in Show Business is one that voters should keep in mind at the end of the year. From its tag line — "Are you read to feel good?" — on down, Universal is selling "Get On Up" as a high-energy hoot rather than an artist-and-his-struggle biopic along the lines of "Ray," but while the early reviews are not without their reservations, they agree the movie manages to pay ample tribute to Brown's unparalleled skills as an entertainer while peeking behind the music as well.

Reviews of "Get On Up"

Scott Foundas, Variety

Perhaps it’s fitting that a movie on a subject as polymorphous as Brown never quite settles on a style or a tone. Rather than following standard chronological-biopic convention, the script by British playwright Jez Butterworth (“Jerusalem”) and his brother John-Henry splinters the narrative into a series of nonlinear fragments, hopscotching across Brown’s life like a rock skimming a turbulent stream. One minute it’s 1964 and Brown — then the lead singer of the Famous Flames — is upstaging the Rolling Stones at the recording of the seminal concert film “The T.A.M.I. Show.” Then, on a dime, it’s back to 1949 and the teenage Brown’s arrest on petty theft charges.

Alonso Duralde, The Wrap

f you thought the recent “Jersey Boys” was stodgy and problematic, here's a music movie that avoids that other film's pitfalls: It places Brown (Chadwick Boseman, in an electrifying performance) into a specific cultural and political context, while also spelling out to a mass audience the musician's innovations as a performer, artist, and businessman. At the same time, “Get on Up” never skids into puff-piece territory; the film shows us that Brown could be a devoted friend but also an insufferable egotist; a loving husband who could, in turn, be abusive to his wives; and a shrewd money manager who also found himself in debt after a series of misguided entrepreneurial decisions.

Tim Grierson, Screen Daily

When "Get On Up" hints at the reasons why Brown behaved this way — for instance, he was abandoned by his parents and forced to live in his aunt’s brothel — the filmmakers don’t oversell their theories as some grand revelation. Instead, because "Get On Up" shifts across decades, pursuing thematic connections as opposed to biographical plot points, the movie feels like a meditation on Brown, not a definitive CliffsNotes on why he’s regarded as one of pop music’s most important artists.

Sheri Linden, Hollywood Reporter

In sync with its subject, director Tate Taylor’s movie, too, can be wearying, especially in the strenuously scrambled chronology of its early sequences. But under the guidance of producer Mick Jagger, it’s that rare musician’s biography with a deep feel for the music. And in Chadwick Boseman, it has a galvanic core, a performance that transcends impersonation and reverberates long after the screen goes dark.

[blogs.indiewire.com]

Re: Mick: 'Get On Up' film & HBO TV series

Posted by:

Stoneage

()

Date: July 30, 2014 19:17

How are music biographies doing at the box office? Considering the shite flogged at stupid kids at cinemas today it makes you wonder.

Animated cartoons and fantasy seems to be the thing now. Will these kids pay to watch a funk icon from the sixties?

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2014-07-30 19:21 by Stoneage.

Animated cartoons and fantasy seems to be the thing now. Will these kids pay to watch a funk icon from the sixties?

Edited 1 time(s). Last edit at 2014-07-30 19:21 by Stoneage.

Re: Mick: 'Get On Up' film & HBO TV series

Posted by:

latebloomer

()

Date: July 31, 2014 04:42

Fantastic, but very long profile of James Brown in The New Yorker. I can't even get through it all right now, but here's a few snippets:

"This guy was James Brown. He was twenty-two years old, a lithe, rippling sinew of a man, on parole after three years in the state-penitentiary system. He had been locked up at the age of fifteen for stealing from parked cars in Augusta, where he was raised in a whorehouse run by his Aunt Honey. He was a middle-school dropout, with no formal musical training (he could not read a chart, much less write one), yet from early childhood he had realized in himself an intuitive capacity not only to remember and reproduce any tune or riff he heard but also to hear the underlying structures of music, and to make them his own."

"Mr. Brown, as he insists on being addressed, has described himself as “the Napoleon of the stage,” and, like the French emperor, he has a compact body, with a big head and big hands, and a taste for loud, tightly fitted costumes. One evening not long ago, in a dressing room at the great Art Deco pile of the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California, as his valet Roosevelt Johnson ironed a gold lamé suit with heavily fringed epaulettes for the night’s performance, Mr. Brown sat before a mirror contemplating his reflection. His totemic hair—an inky, blue-black processed pompadour, “fried, dyed, and laid to the side”—was bunched up in curlers, awaiting release. A black silk shirt hung open from his shoulders, baring a boyishly smooth and muscular torso for a man who says he’s sixty-nine and is alleged by various old spoilers down South to be as much as five years older. He had just finished refurbishing the thick greasepaint of his eyebrows and, wielding a wedge-shaped sponge, was lightening the upper edges of his high, flat cheekbones with some latte-colored paste. He studied his smile, a wide, gleaming streak of dental implants whose electrifying whiteness might have made Melville blink. In show business, he has said, “Hair is the first thing, and teeth are the second. Hair and teeth. A man got those two things, he’s got it all.” Still, he looked tired and lonely and even smaller than he is, as old men tend to look when applying their makeup.

In performance, however, he makes the stage look small, and wears his years with a survivor’s defiant pride. James Brown is, after all, pretty universally recognized as the dominant song-and-dance man of the past half century in black-American music, perhaps in American popular music as a whole: he is the source of more hits than anyone of any color after Elvis Presley. He stands virtually unrivalled as the preëminent pioneer and practitioner of the essential black musical styles of the sixties and early seventies—soul and funk—and the progenitor of rap and hip-hop. Since 1968, however, he has had only one Top Ten hit, “Living in America,” from the 1985 soundtrack to Sylvester Stallone’s “Rocky IV,” which was followed by a period of seeming ruin, marked by serial scrapes with the law on charges of spousal abuse (later dropped) and drug possession, and a return to jail, from 1988 to 1991, after he led a fleet of police cars on a high-speed chase back and forth across the Georgia-South Carolina border. Yet his iconic stature as an entertainer has steadily increased in the decade since his release, and his return to the stage."

"He is a showman of the old school, equal parts high artist and stuntman, and his boldest moments leave art and stunt indistinguishable.

This is never more evident than at the point in his show—during “Please, Please, Please”—when he cuts from the peak of a feverish vocal and instrumental crescendo and collapses to his knees in stunned silence. His band simultaneously fades to a worried murmur of pulsing rhythms, while the audience, as he puts it, falls “so quiet you can hear a rat peelin’ cotton,” and in a high, pleading quaver, he announces, “I feel like I’m gonna scream.” The crowd goes silent as he sinks even lower to the floor and lets the beats pass. “You make me feel so good I wanna scre-e-eam,” he wails. The crowd roars, he falls still, and when the crowd settles down he wails again, “Can I screeeeam?” And again: “Is it all right if I screeeeeeeeeeeam?” The crowd appears fit to riot. He appears fit to be tied. Then he screams. The scream has a sound of such overwhelming feeling that you cannot believe the man controls it. The impression, to the contrary, is that he is controlled by it, as if out of all the throats in the cosmos it had found his, and rendered him wild: the sound in the wild man’s throat from beyond the wild man’s consciousness that is the wild man’s being."

....and that's just in the first third of the article. Have fun with it, if you're so inclined.

Link to full article: [www.newyorker.com]

"This guy was James Brown. He was twenty-two years old, a lithe, rippling sinew of a man, on parole after three years in the state-penitentiary system. He had been locked up at the age of fifteen for stealing from parked cars in Augusta, where he was raised in a whorehouse run by his Aunt Honey. He was a middle-school dropout, with no formal musical training (he could not read a chart, much less write one), yet from early childhood he had realized in himself an intuitive capacity not only to remember and reproduce any tune or riff he heard but also to hear the underlying structures of music, and to make them his own."

"Mr. Brown, as he insists on being addressed, has described himself as “the Napoleon of the stage,” and, like the French emperor, he has a compact body, with a big head and big hands, and a taste for loud, tightly fitted costumes. One evening not long ago, in a dressing room at the great Art Deco pile of the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California, as his valet Roosevelt Johnson ironed a gold lamé suit with heavily fringed epaulettes for the night’s performance, Mr. Brown sat before a mirror contemplating his reflection. His totemic hair—an inky, blue-black processed pompadour, “fried, dyed, and laid to the side”—was bunched up in curlers, awaiting release. A black silk shirt hung open from his shoulders, baring a boyishly smooth and muscular torso for a man who says he’s sixty-nine and is alleged by various old spoilers down South to be as much as five years older. He had just finished refurbishing the thick greasepaint of his eyebrows and, wielding a wedge-shaped sponge, was lightening the upper edges of his high, flat cheekbones with some latte-colored paste. He studied his smile, a wide, gleaming streak of dental implants whose electrifying whiteness might have made Melville blink. In show business, he has said, “Hair is the first thing, and teeth are the second. Hair and teeth. A man got those two things, he’s got it all.” Still, he looked tired and lonely and even smaller than he is, as old men tend to look when applying their makeup.

In performance, however, he makes the stage look small, and wears his years with a survivor’s defiant pride. James Brown is, after all, pretty universally recognized as the dominant song-and-dance man of the past half century in black-American music, perhaps in American popular music as a whole: he is the source of more hits than anyone of any color after Elvis Presley. He stands virtually unrivalled as the preëminent pioneer and practitioner of the essential black musical styles of the sixties and early seventies—soul and funk—and the progenitor of rap and hip-hop. Since 1968, however, he has had only one Top Ten hit, “Living in America,” from the 1985 soundtrack to Sylvester Stallone’s “Rocky IV,” which was followed by a period of seeming ruin, marked by serial scrapes with the law on charges of spousal abuse (later dropped) and drug possession, and a return to jail, from 1988 to 1991, after he led a fleet of police cars on a high-speed chase back and forth across the Georgia-South Carolina border. Yet his iconic stature as an entertainer has steadily increased in the decade since his release, and his return to the stage."

"He is a showman of the old school, equal parts high artist and stuntman, and his boldest moments leave art and stunt indistinguishable.

This is never more evident than at the point in his show—during “Please, Please, Please”—when he cuts from the peak of a feverish vocal and instrumental crescendo and collapses to his knees in stunned silence. His band simultaneously fades to a worried murmur of pulsing rhythms, while the audience, as he puts it, falls “so quiet you can hear a rat peelin’ cotton,” and in a high, pleading quaver, he announces, “I feel like I’m gonna scream.” The crowd goes silent as he sinks even lower to the floor and lets the beats pass. “You make me feel so good I wanna scre-e-eam,” he wails. The crowd roars, he falls still, and when the crowd settles down he wails again, “Can I screeeeam?” And again: “Is it all right if I screeeeeeeeeeeam?” The crowd appears fit to riot. He appears fit to be tied. Then he screams. The scream has a sound of such overwhelming feeling that you cannot believe the man controls it. The impression, to the contrary, is that he is controlled by it, as if out of all the throats in the cosmos it had found his, and rendered him wild: the sound in the wild man’s throat from beyond the wild man’s consciousness that is the wild man’s being."

....and that's just in the first third of the article. Have fun with it, if you're so inclined.

Link to full article: [www.newyorker.com]

Re: Mick: 'Get On Up' film & HBO TV series

Posted by:

TeddyB1018

()

Date: July 31, 2014 06:10

Mick's doing what he's been wanting to for a while. Good for him. I'm not personally that optimistic about the HBO show, not being a fan of some of the creative team, but it's likely to make a big splash and be on air for a few years at least.

'Get On Up'

Posted by:

bye bye johnny

()

Date: July 31, 2014 21:25

Richard Corliss says it's "Star Time" - for Chadwick Boseman.

REVIEW: Get On Up Is a Loud, Proud and Oscar-Worthy James Brown Biopic

Universal Pictures